Ms. Warren’s campaign and her allies, convinced her message is being ignored, see a path forward — and they say writing her off would be a mistake.

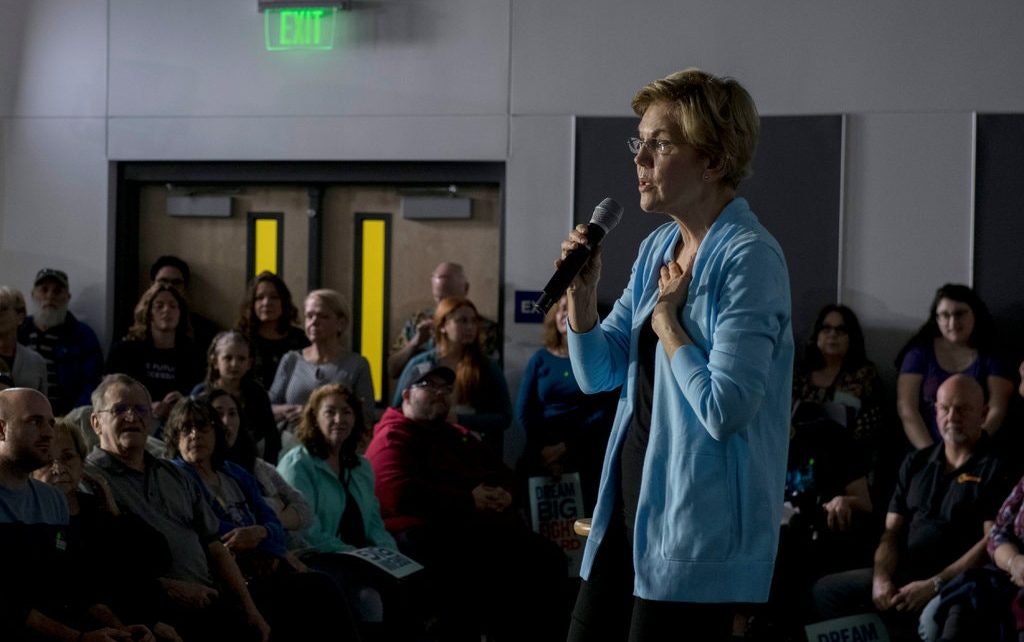

RENO, Nev. — A bad month for Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts keeps getting worse. She finished in a respectable third place in the Iowa caucuses, but a results-tallying meltdown muddled what could have been a good evening. New Hampshire was better at logistics but worse for her candidacy, considering she ended up closer to candidates who dropped out after the primary than those who finished on top.

On Sunday, Ms. Warren had a cold so severe it threatened to sideline one of the country’s most famous persisters.

“People told me, ‘You have to cancel your day in Reno,’” Ms. Warren said, hoarse and barely audible. “I said, ‘Reno has been left out of way too many conversations.’”

Ms. Warren and her team feel the same. She is not cratering or surging, neither the most likely to win nor at risk of immediately dropping out, a 40-degree day surrounded by candidates who are hot and cold. Her staff members and plenty of allies argue that as a result, she is being ignored by the news media and some voters during a pivotal moment in the primary, and she is at risk of becoming less relevant in the nominating process — something her campaign is now trying to reverse.

When her caucus-night speech in Iowa was cut off, her campaign aides complained privately to cable networks. When her speech after the New Hampshire primary was not carried live at all, they took their criticism public.

“Elizabeth hasn’t been getting the same kind of media coverage as candidates she outperformed,” read a recent fund-raising email to supporters. “We can’t count on the media to cover our campaign fairly, so we’re taking our case directly to voters.”

If the campaign is trying to rally supporters at a time when Ms. Warren’s candidacy hangs in the balance, it is also trying to move on from some recent political events: Her much-touted campaign organization did not show a dramatic payoff in the first two contests, and polling in Nevada, South Carolina and Super Tuesday states has shown little improvement among the black and Latino Democrats she once thought could spring her to the nomination.

Straining themselves to avoid criticizing the candidate or campaign, Ms. Warren’s most loyal admirers are trying to reframe the New Hampshire outcome in the most flattering light possible: More than two dozen of them, in interviews at events throughout Nevada, argued her fourth-place finish was an aberration, not a blow to the campaign’s core message that should force reflection or correction.

Few admitted disappointment in the outcome of the first two contests and a growing sense of pessimism about Ms. Warren’s electoral prospects. But many of her die-hard backers, the true believers, have gone on the offensive, arguing that the only trouble she faces is that political observers are prematurely writing off the campaign.

At events in Nevada, backers rattled off talking points, highlighting polling that showed her with more support among nonwhite voters than Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and former Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind. They noted her large staff on the ground in states that vote on Super Tuesday. They criticized the “corporate media” in ways that echoed supporters of Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

“She’s a female candidate, and the media hasn’t taken her seriously,” said Matt Newton, 46. “They give so much attention to the male candidates.”

Pat Campbell-Cozzi, 76, said flatly: “New Hampshire doesn’t matter. I know where she’ll be after the final vote.”

Heather McGhee, the former president of the progressive think tank Demos, said it was up to these grass-roots supporters to reverse the direction of Ms. Warren’s candidacy.

“Her supporters have been the ones to have her back and make that rallying cry,” said Ms. McGhee, who is close to Ms. Warren’s team.

“Even in New Hampshire, these voters are very fluid,” she said. “Forty eight percent decided in the last two days, and that just means the race is very much up for grabs.”

In some ways, this dynamic brings Ms. Warren’s campaign back to where it started. When she announced her presidential run, she was considered a political figure in the shadow of Mr. Sanders on the left and fresher faces toward the center, such as former Representative Beto O’Rourke of Texas and Senator Kamala Harris of California.

Supporters would complain about her being ignored, as male candidates such as Mr. O’Rourke commanded major early attention. Questions loomed about whether Ms. Warren could raise enough money to keep her large organizing staff afloat.

Throughout the summer, she used policy to help set the tone of the race, shaping the early debates and leading other candidates to face questions about her proposals. But as voting has moved from a hypothetical to a reality, and the primary has stopped being a contest of ideas, Ms. Warren has struggled to adjust.

Fund-raising concerns have returned, and the campaign has set a goal of raising $7 million before the Nevada caucuses. In a recent video, Ms. Warren told supporters: “I need to level with you: Our movement needs to raise critical funds so I can remain competitive in this race through Super Tuesday.”

Ms. Warren currently ranks fourth among the Democratic presidential candidates in mentions on cable news, behind Mr. Sanders, former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. and Mr. Buttigieg, according to the Internet Archive’s Television News Archive.

She has frequently brushed off questions that ask her to reflect on her own media coverage, saying that she tries not to read stories about herself and her campaign.

On Tuesday, she showed no signs of the annoyance that has rankled her supporters, energetically pitching herself to union voters, hosting a town hall event in Henderson, Nev., and attending a Latino market.

Her schedule in Nevada includes events with the actress Yvette Nicole Brown, the former cabinet secretary Julián Castro, and Representative Deb Haaland of New Mexico. More campaign staff members and surrogates have hit the television circuit in recent days, including black and Latino supporters who aim to serve as community validators for voters with whom Ms. Warren needs to develop trust.

Supporters and allies are doing their part to generate excitement, New Hampshire be damned. Organizations that are supporting Ms. Warren have blasted out emails with subject lines like “Warren the Warrior Wonk Returns — and people LOVE it,” sent after Ms. Warren criticized one of her favorite targets, Michael R. Bloomberg, the former New York mayor and a presidential rival. On Monday, which was Presidents’ Day, Ms. Warren’s supporters helped make #PresidentWarren a national trending topic on Twitter.

“Elizabeth is third in delegates, has over a million grass-roots donors, and is drawing thousands of people to her events,” said Kristen Orthman, Ms. Warren’s communications director. “The pundits have consistently been wrong about this primary and that’s why it’s important for people to organize for and support the candidate they believe in rather than the candidate the coverage says is on top.”

One undecided voter who attended Ms. Warren’s event in Reno said her performance in New Hampshire had sent a troubling message, considering that the state shares a border with Massachusetts.

“It was concerning — do they know something I don’t?” Kristin Ritenhouse, 49, said of New Hampshire voters. “Because my neighbors like me.”

Jocelyn Waite, 66, a caucus captain who also attended the rally, recited the campaign email that was critical of press coverage almost word for word. Ms. Waite said the last week had taught her that “corporate media doesn’t want” Ms. Warren to win.

“Aren’t there supposed to be three tickets out of Iowa? She was third and that wasn’t good enough,” Ms. Waite said. “And then, in New Hampshire, third was good enough for Klobuchar.”

Grievance can be a powerful motivator for political campaigns, bonding supporters against a common enemy, driving small-dollar donations and volunteers, and helping to create an organic network of support, particularly online and on social media.

President Trump has, in the extreme, railed against the news media and other political enemies. Democratic candidates like Mr. Sanders and Mr. Biden have also tried to unite supporters through rhetoric that downplays the significance of traditional political gatekeepers, though they have never approached the president’s tenor.

But the tactic can also be a sign of a campaign in decline. Supporters of Ms. Harris, Mr. O’Rourke, Mr. Castro and Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York all criticized outside factors, such as media coverage and the debate rules set by the Democratic National Committee, before their favored candidates exited the race.

Martha Zimmerman and Natalie Buddiga, who attended Ms. Warren’s rally in Reno, both said they felt she was being counted out of the race too early. But they also admitted to a sense of despair that was quietly setting in.

“I just don’t run into other Elizabeth Warren fans, and I’m always meeting these Bernie die-hards,” said Ms. Buddiga, 25, who wore a shirt that read “The Future is Female.”

Ms. Zimmerman, 29, a self-described voracious consumer of political media, said the past week had been difficult. While sexism cannot be separated from analysis of Ms. Warren’s candidacy, she said, neither could the reality of her performance in New Hampshire.

In recent days, she considered changing her vote to Mr. Sanders, a candidate she felt had a better chance at the nomination.

She decided against it.

“We’ve got to stand with our girl,” she said. “We have to persist like she would.”

Source: Elizabeth Warren’s Allies Claim ‘Erasure’ As They Seek To Reignite Campaign