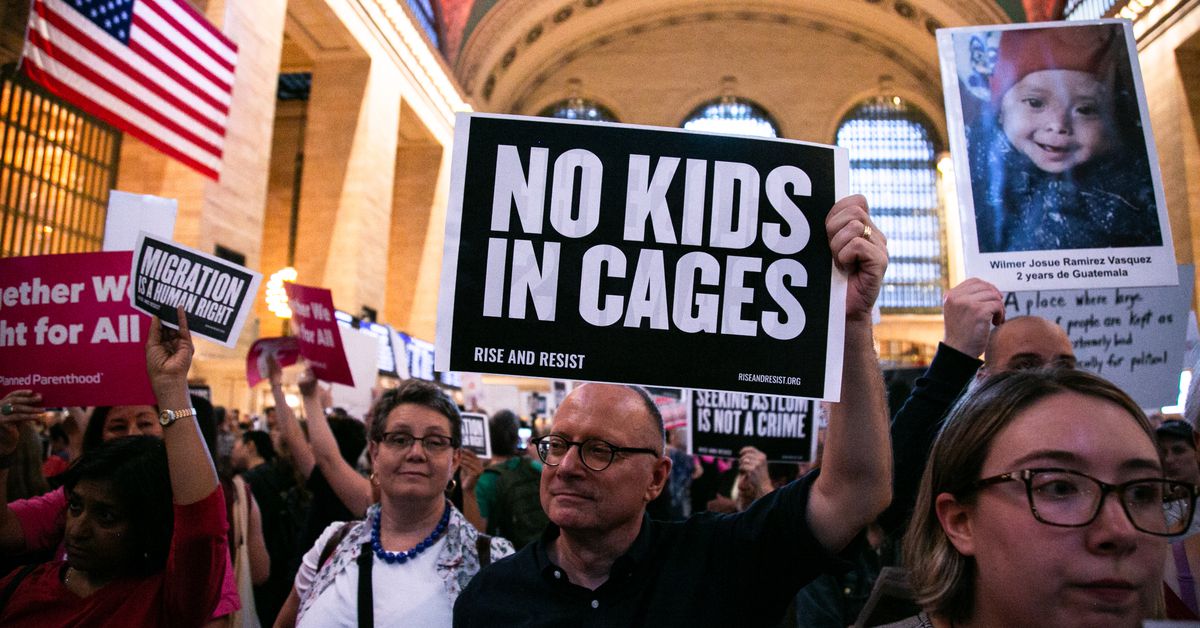

A federal judge just told the government to release migrant children or explain why they need to remain in detention.

A federal judge on Saturday confronted the Trump administration on its treatment of an especially vulnerable population — migrant children in US custody — as the coronavirus pandemic rages.

Judge Dolly Gee of the US District Court in Los Angeles instructed the Health and Human Services Department (HHS) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on Saturday to either promptly release migrant children from custody or explain why they must be kept in detainment amid the pandemic, which has killed more than 2,500 in the US as of March 30, according to the New York Times.

If the agencies fail to do so by April 10, Gee said she will order the government to release about 3,400 children in HHS custody and hundreds more in ICE family detention centers, to either their family members or foster parents. She also said she decided against ordering their immediate release due to the risk of exposing them to the virus, given current travel restrictions.

While children generally have a low risk of becoming seriously ill due to the coronavirus, four children in HHS custody — all of which are housed at facilities in New York — have already tested positive and may have spread it to others, including caretakers and people with underlying health conditions who are more likely to face severe complications.

Because coronavirus poses “unprecedented threats” to the children themselves and those who interact with them, Gee ruled that keeping them in detention likely violates a decades-old agreement that lays out basic standards for their care.

That agreement — known as the the “Flores settlement” — mandates that the government release migrant children “without unnecessary delay,” and keep them in “safe and sanitary conditions” in the meantime.

Gee also appointed an independent monitor to ensure that the government is maintaining such conditions for children in its detention facilities, which she described as “hotbeds for contagion.”

It’s not the first time federal courts have found detention conditions for migrant children lacking. Well before the coronavirus hit, Gee ordered the government to provide migrant children with basic necessities, including toothbrushes and soap, under the same settlement agreement.

The government’s measures to curb coronavirus in immigration detention aren’t enough

The government has made efforts to mitigate the spread of coronavirus in its immigration detention facilities, which house both children and adults, but social contact still poses a serious risk to vulnerable populations.

HHS has stopped sending children in its custody to New York, California, and Washington state, which currently have the highest numbers of confirmed coronavirus cases in the US. It also requires twice-daily temperature checks of children in custody, provides Covid-19 testing, and isolates those found to have tested positive for the virus. (It has not, however, instituted social distancing in its facilities so far.)

ICE, which has 38,000 immigrants in detention in more than 130 private and state-run facilities nationwide, was comparatively slower to respond to the pandemic. Only as of March 27 — and only after outcry from immigrant advocates — did ICE begin distributing hand sanitizer and soap more widely to detainees. It also instituted more regular and thorough cleaning in common areas, put schooling on hold in certain states, and encouraged social distancing at mealtimes and in common areas.

But it hasn’t announced any plans to release immigrants, many of whom have no previous criminal convictions.

Despite these measures, medical experts nevertheless fear that immigrants in detention remain particularly vulnerable to Covid-19, the illness caused by the novel coronavirus. Detainees housed in tight quarters can’t maintain social distancing, and medical resources — including personnel, testing kits, and personal protective equipment — are limited in detention centers.

Lawmakers and advocates have been calling for their release, especially for detainees who are older or have underlying health conditions that make them more susceptible to the virus. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, that includes people with blood disorders, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, compromised immune systems, current or recent pregnancy, endocrine disorders, metabolic disorders, heart disease, lung disease, and neurological and neurodevelopmental conditions.

The American Civil Liberties Union and the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project have already sued ICE to seek the release of vulnerable detainees at one detention center in Tacoma, Washington, which is just outside Seattle, the original epicenter of the Covid-19 outbreak in the US.

Children themselves don’t appear to be vulnerable to the virus unless they have a preexisting health condition that puts them at risk. But the effects of social isolation in detention can be particularly harmful to them, exacerbating psychological trauma and mental health issues during a critical developmental period. They may also be able to carry the virus without exhibiting symptoms, potentially spreading it to those with whom they come in contact.