As the coronavirus pandemic continues its rampage across the United States, with more than a million confirmed cases and no end in sight, medical professionals and experts say the strain on the health care system has exposed major flaws and taught hard lessons.

They said the pandemic has shown that we need to shift the way we think about health care as overwhelmed hospitals struggle to treat the surge in patients and lack enough personal protective equipment to keep workers safe.

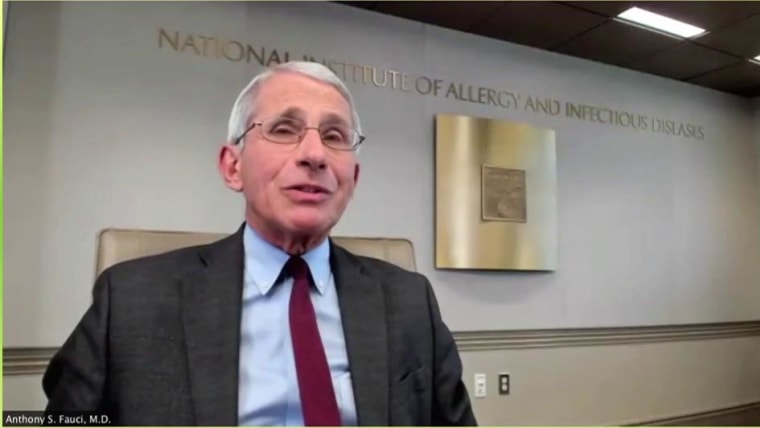

“We essentially have built a health care system that is perfectly right-sized for the care that was delivered yesterday, with totally just-in-time supply chains because we value efficiency,” said Dr. Brendan Carr, chair of emergency medicine for the Mount Sinai Health System in New York. “And what just happened to us is we got caught out on that, and it became very, very clear that we weren’t ready for an unexpected bump in the night.”

In New York City, he said, “it took two weeks, three weeks, until we totally broke the financial model of health care.”

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Health care experts urged the industry to heed the tough lessons learned during the pandemic for the future of medicine, and they called for a change in financial incentives, a more national and global approach to public health, the creation of an efficient manufacturing and distribution system for critical supplies, and a continued increase in the use of telemedicine.

‘A broken system’

Carr said that in New York City, the center of the virus in the U.S., there has been “a total pause on almost everything that we understand as health care,” including scheduled outpatient visits, procedures and operations, as well as chemotherapy treatments — which are major revenue streams for hospitals.

He said primary care was a low-margin to negative-margin business for hospitals, while “fancy operations and cancer therapy and things of that nature are high margins, what makes health care systems stable to offset the losses from primary care.”

A change in how health care businesses are run would likely be determined either by congressional action or by creating payment incentives for hospitals, Carr said.

If there were a congressional bailout for health care systems and business resumed as normal, he said, some systems would stockpile more, and some might be more mindful about workflows and increasing social distancing in facilities.

“But I’ve got to tell you that feels like moving deck chairs around on the Titanic to me,” he said. “Those are responses to a broken system, and the big fixes that are out there can’t be done at the hospital level. They have to be done either with regulatory reform or through payment reform.”

Dr. Hardeep Singh, a professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, said hospitals have also typically run at near-maximum capacity and do not want to have excess beds because of financial incentives.

“But that has cost us in terms of problems in this day and age, so I think preparedness and having that surge capacity going forward” would be critical in the future, he said.

“We generally in health care do things reactively, and I think what this episode has taught us is we need to be a lot more proactive,” he said.

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

Singh said the pandemic has showed that the U.S. should “absolutely” start relying more on domestic manufacturing of lifesaving personal protective equipment and ventilators, which were in short supply and high demand from manufacturers in China.

In addition, it is critical to have effective distribution channels and national data sharing, he said.

“We just don’t have a national or regional sort of spine of all the data elements that we need to figure out where do we allocate resources next,” he said.

Singh stressed the importance of building a public health infrastructure in which the U.S. could identify which areas and hot spots will need the most supplies. The national infrastructure could also be used in future crises.

“You don’t know what’s going to affect us five or 10 years down the line,” he said.

‘A national security health issue’

Dr. Paul Biddinger, director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Center for Disaster Medicine, said he expected many health care systems, including his own, to start stockpiling equipment.

He also hopes to see major changes at the national level in the distribution of supplies.

“In this arena, we have to have an excess capacity for events exactly like this, treating it like a national health security issue, just like we would with military supplies to defend the nation. This is a version of protecting the nation,” he said.

Patricia Davidson, dean of the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, said the pandemic also showed the need for more national and global governance in public health.

Davidson cited states’ creating competition when they individually tried to buy protective equipment and ventilators, which drove up prices and left them scrambling.

“I really hope that we’ll be able to learn some really important lessons and people can collaboratively come together to make better solutions,” she said.

Regional or national coordination of stockpiles of equipment or ventilators would be a challenge, she said, and it is important to develop a system that would allow for “considered management of inventory and rotating things out.”

“This is a really complex undertaking, but what’s clear is individual, small, stand-alone community hospitals can’t deal with this,” she said.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

The speed with which the virus became a worldwide outbreak also highlights the need for more global governance in health care and the empowerment of agencies like the World Health Organization, Davidson said.

“There needs to be a realization that we’re each on the planet interconnected. Viruses don’t know borders,” she said.

Behaviors learned

The experts said the speed with which the medical system had to adapt to the pandemic led the health care industry to boost access to telemedicine.

“I think medical care in so many different ways will be transformed with the really increased use of telemedicine,” Biddinger said. “I think this hopefully will be better for patients and for providers for the subset of visitors where you don’t really need to physically come in to see your doctor.”

Biddinger also hopes increased attention to hand hygiene and increased use of protective equipment could reduce the spread of infectious diseases within hospitals.

“Even in the medical setting, lots of people took a reasonably casual approach to personal protective equipment,” he said. “They weren’t quite as careful about how they took off their gloves or gowns or their masks. They weren’t quite as good at hand hygiene.

“I think that’s now pretty ingrained in a lot of people. There’s a possibility we could see a decrease in hospital-acquired infections, which would be fantastic,” he said.

But other learned social behaviors could have negative impacts in the long term, Singh said.

“People have been afraid to go into health care [facilities] even if they have actually alarming symptoms, and we’re afraid that people would be getting harmed sitting at home and not seeking treatment,” Singh said.

Source: Health care experts say coronavirus exposes major flaws in medical system